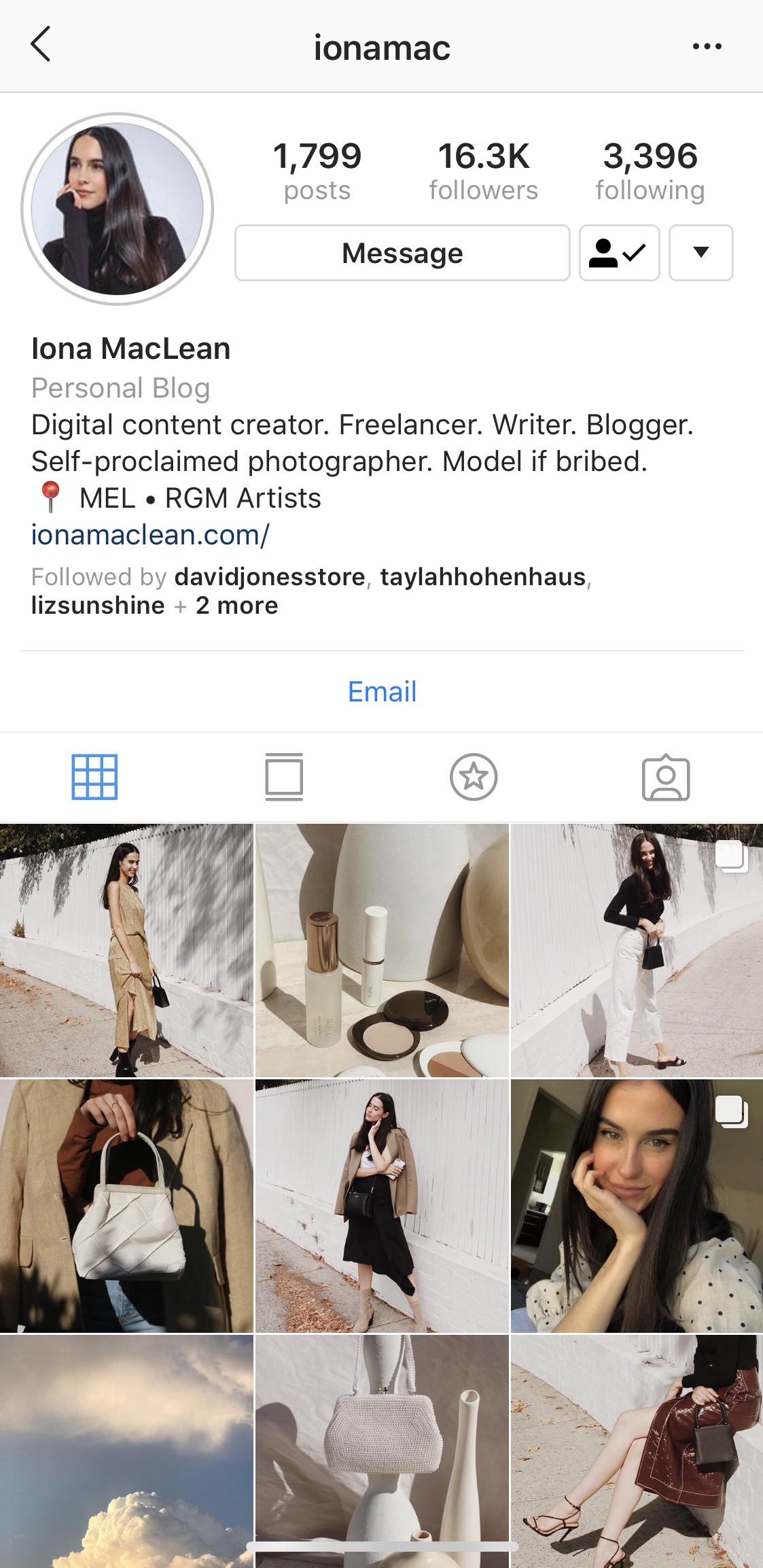

The popular burger joint in Sydney controversially posted an Easter Facebook ad earlier this year that read: ‘Jesus got hammered for his sins, you can too’ (refer to image 1).

On the 17th of April 2019; Mary’s Newtown posted an announcement on their Facebook page to inform their followers of their opening hours over the Easter long weekend. This post backfired when multiple consumers and followers deemed the post ‘disrespectful’, ‘disgusting’, and urging them to remove the post (Burnie, 2019). This escalated even further by a Facebook group lead by Orthodox Christian’s who encouraged followers to post negative comments about the business in retaliation to the post (Foster, 2019). The co-owner of Mary’s reportedly stated that the post wasn’t meant to offend anyone (Forster, 2019). As a small local business a case like this, caused by a combination of mismanagement and misunderstanding; can have impactful consequences where reputation is damaged.

The rising emergence of social media raises ethical concerns about the potential to facilitate deception, social grooming and this case, the creation of defamatory content (Sweney and Gosden, 2006). There was an absence of self-reflection that Mary’s did not perceive any offence within the post.

The contribution of this facet has impacted Mary’s fail, as consumers are able to voice their opinions where morality does not always come into play. The vernacular affordances of social media are sharing, liking, disliking and reporting content. This can make hiding publicly displayed content difficult. Facebook is a platform that helps you connect and share with the people in your life (Graham, 2019), it promotes behaviours of ‘compulsory publicness’. It grants a consumer choice of what to post and share- it is wholly up to the discretion of the user.

Social media ethics can be seen as a human concern, in which people have control over the way technology is utilised. Light and McGrath (2010) state that users are thus, “able to design systems and employ preventative measures to guard against the likelihood of undesirable behaviours and outcomes.” Consequentialism should be noted of a user’s actions, as it is their duty and moral characteristics that need to be taken into consideration of others’ emotions and rights.

An important ethical component of using social media as a marketing tool for a business is to ensure that peoples beliefs are not trodden on/ upset/ offended; or their beliefs are not taken advantage of. Some companies have used a shock approach marketing effect to advertise their products, which would have been considered as an advantage gained by the additional attention (a positive impact), in comparison to the customer loss. In the case of Mary’s, there was no shock attention intended, in this case, not all publicity is positive. The consumer reaction was very negative in regard to the intended message of the post. This can be due to technology developers holding a user-oriented view; they regulate particular aspects of interaction through privacy and acceptable-use policies, and the rest is left up to the user’s choice and their views of morality (Light; Mcgrath, 2010).

Interpersonal ethics is another element that links into morality and virtuous ethics. Mary’s Easter post breached social standards, however there is a mutual responsibility which is shared between the user and Facebook as a platform. There is no simple binary between the platform and user, as each shape one another; however, users are responsible for their sharing of certain content. In the case of Mary’s, the post wasn’t overtly offensive, in that it didn’t set out to attack religion or beliefs. Mary’s needed to take responsibility for the post and enact procedures to ensure it doesn’t arise again. Social media platforms need to develop and promote healthy online policies (Gillespie, 2017), in order for businesses such as Mary’s, to not get as viciously damaged from one un-intentional post.

To avoid the fail, as a sole responsibility the user must correctly regulate their online content (Brock, 2016). A crucial factor is to implement checking procedures between multiple entities who share different perspectives. Establishing a small test group between employees and some consumers outside of the business will help in determining consumer reaction. This is because one person’s perspective does not cover a large enough segment of the customer base to determine the level of appropriateness of a post.

As a director of the business, key prohibited areas should be established and not be publicly discussed on social forums. Each post should be coedited and approved by the owner of the business. Mary’s did not have a correct understanding of their target market and therefore were unable to connect and use the influence of spreadable media to their advantage.

References

- Brock, G. (2016). Ctrl Z: The Right to Be Forgotten. NYU Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/stable/j.ctt1803zhx

- Burnie, A. (2019). Mary’s Newtown Lambasted Over “Satanic” Jesus Christ Easter Ad. Retrieved from https://www.bandt.com.au/campaigns/marys-newtown-lambasted-disgusting-jesus-christ-easter-ad

- Foster, A. (2019). Australian pub slammed for ‘disgusting’ Easter post about Jesus. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2019/04/19/australian-pub-slammed-for-disgusting-easter-post-about-jesus/

- Gillespie, T. (2017). Regulation of and by platforms. In J. Burgess (Ed.)., The sage handbook

- of social media (254-278). Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Graham, T. (2019). New Media Ethics, Divides and Non- Participation. Retrieved from https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_142802_1&content_id=_7846358_1

- Light, B., & McGrath, K. (2010). Ethics and social networking sites: a disclosive analysis of Facebook. Information Technology & People, 23(4), 290-311. doi: 10.1108/09593841011087770